How a Beloved Character Actor Became One of Our Finest Critics

Jason Guriel on Simon Callow and his new Orson Welles biography

ONE-MAN BAND, THE third installment in Simon Callow’s biography of Orson Welles, arrives nearly a decade after the last, 2007’s Hello Americans, and nearly twenty years after the first, 1997’s The Road to Xanadu. This isn’t unusual; multipart biographies tend to be the product of tectonic plates, their individual volumes mountaining up after much research, soul-searching, rumbling. But the dazzling entries in Callow’s life of Welles, which he began in 1989, are closer to comets, the sort that fanboys track and log. In other words, One-Man Band is a cultural event. It’s like getting a new installment of Star Wars, except better, and we already know what happens.

Or do we? The romantic view is that Welles was a prodigy who singlehandedly revolutionized whichever medium was at hand. After mastering theatre and radio in the 1930s, he addressed himself to motion pictures and immediately produced a masterpiece, Citizen Kane (1941). But Welles shorted out relationships almost as quickly as he electrified audiences. For the rest of his life, the writer-actor-director struggled to finance projects, and saw the work he did complete wrenched away and re-cut by a motley of producers, philistines, and other enemies of art. By the 1980s, his iconic baritone was reduced to supplying Hasbro’s Unicron with gravity.

“[M]ultipart biographies tend to be the product of tectonic plates, their individual volumes mountaining up after much research, soul-searching, rumbling.”

Callow’s biography, however, swabs away this layer of myth, thick as actors’ pancake. The first volume, which took us up to the release of Kane, complicated the view of Welles as a volcano in a vacuum, who churned up works of genius on his own. In fact, Welles was more like an inspired consolidator of other people’s ideas, with a flair for editing, lighting, and spectacle—and a fatal tendency to sudden restlessness. The second volume showed how Welles, far from a victim of the studios, often absented himself from his own productions at critical moments—usually the editing stage. “The student of Welles’ life feels like the audience of a melodrama,” writes Callow, as Welles begins to drift away from his 1948 adaptation of Macbeth. “‘Don’t go!’ one wants to cry. ‘Finish the film!’ But off our hero canters, oblivious to the destruction of all his dreams.”

But Callow’s biography of Welles, which will include a fourth volume, does so much more than flush out facts. Callow himself is a celebrated director and character actor—no account of him can seem to resist recalling his memorable turn in Four Weddings and a Funeral—who has brought his experiences to a number of celebrated books. Callow, however, doesn’t simply recount performances and productions; he critiques them, too—and in a distinctive, witty prose style. Callow sometimes has harsh words for critics—it’s an actor thing—but he’s quietly become one of our finest interpreters of what can happen on a stage or screen.

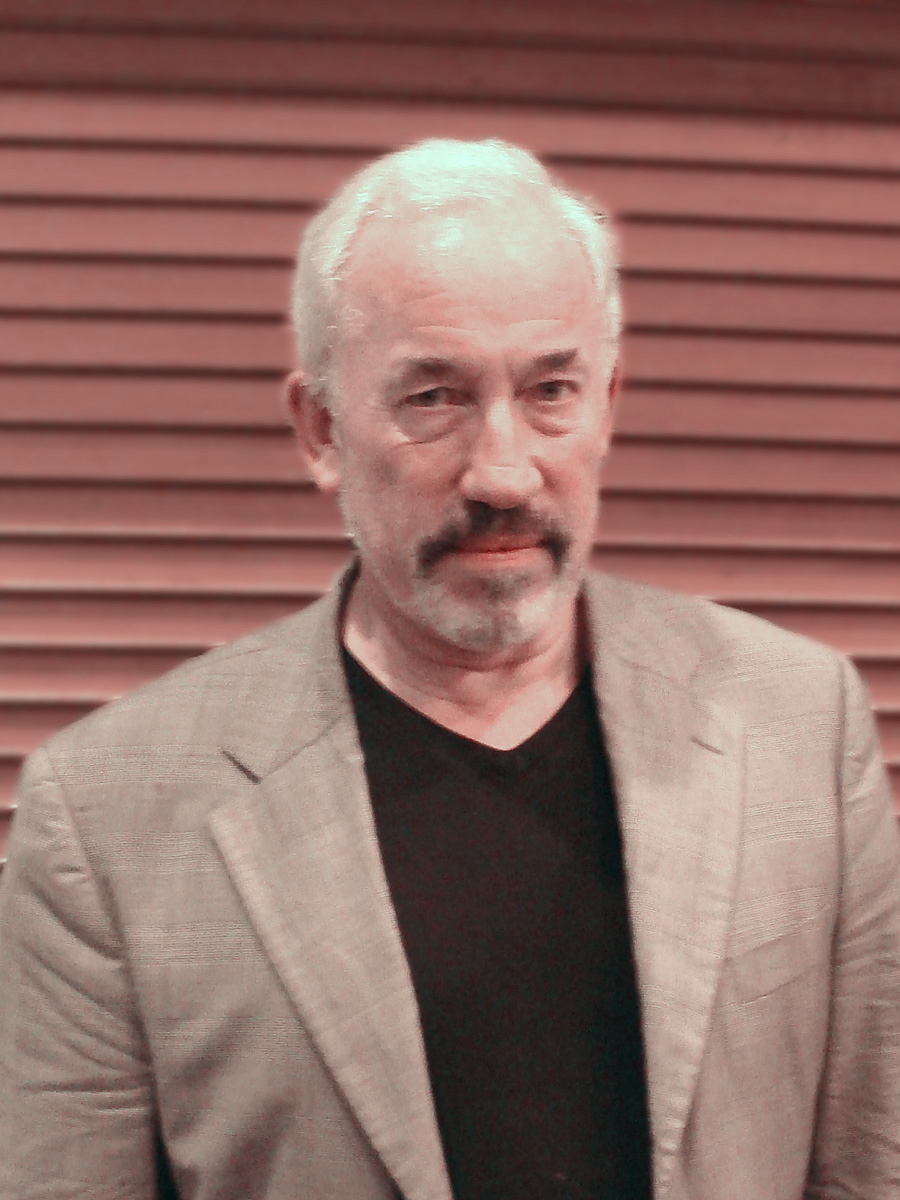

Simon Callow. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

“WHEN I WAS eighteen, I wrote Lawrence Olivier a letter.” So begins Callow’s 1984 memoir Being an Actor—and so began his acting career: writing. (“Language was always the starting point for me,” he later notes.) Amazingly, Olivier posted a response, encouraging the teenager to join the National Theatre company. Callow began in the archetypal mailroom, then graduated to the box office. His breakthrough, during a student play of his own devising, is so vividly reported it should be reproduced in course kits:

In all the anxiety over the show, worrying whether it was clear, whether everybody knew where to come on or go off, I had no time to think about my performance, no time to wonder about its effect on the group…. I just did it. Suddenly for the first time, I was acting. Not performing, or posturing, or puppeteering. I was being in another way.

At a stroke the mask that I had screwed on to my face fell away. I was free, easy, effortless. For the first time since I’d arrived at the Drama Centre I understood what playing a character was. It was giving in to another way of thinking. Giving in was the essential experience.

Being an Actor is a minor classic, part memoir, part textbook, part manifesto. It advances a “thespocentric” vision of theatre, in which actors literally run the show. (Acting, to Callow, isn’t the unstopping of one’s self; it’s the invention of selves.) Being an Actor is also brave; it recounts how Callow came to terms with being homosexual—no mean feat for memoir in the age of Margaret Thatcher.

“Callow sometimes has harsh words for critics—it’s an actor thing—but he’s quietly become one of our finest interpreters of what can happen on a stage or screen.”

But it’s Callow’s commitment to articulating the craft of acting as a form of creation that runs through the book, and the rest of his writing, like a crackle. Here’s a passage from his biography of Charles Laughton, one of his major subjects:

His acting faculty was a thing constructed of a million nerves, a-quiver with impulses. Every impulse, as it passed through him, provoked an adjacent impulse: an entire new set of vibrations was sounded, each with implications. So easy to become lost in a baroque tissue of resonating tendrils. But it is exactly this ability to form a character out of a thousand living cells which together form a breathing, complex organism that fitted him so wonderfully for the screen with its microscopic sensitivity. Watching him can be like watching film of plant life: nature’s kingdom in a man.

Callow is an unflagging prose stylist, for whom description is creative opportunity, an occasion to exercise wit and manufacture metaphor. Unemployment becomes the “primeval slime from which actors emerge and to which, inevitably, they return”; a poem becomes “a piece of wood that the microscope reveals to be, not a solid mass, but a kingdom seething with life, with swarming multitudes of molecules.” Time spent among the warm-blooded—actual writers, actors, and directors—has insulated Callow’s prose against the predations of jargon. (“Orsonolators” is his coinage for “the army of theoretical academics who have moved in on [Welles] like locusts...”)

He also rejects postmodern cant—for example, undergrad-grade assertions that people are unknowable and thorny concepts like “truth” require tongs. The humble goal of theatre critics of yesteryear—“to report and evaluate the gestures invented by actors…to report them, to preserve them, to record their power (or feebleness)”—is pretty clearly his goal, too. In short, Callow belongs to a select tradition that includes figures like Jean-Luc Godard and Welles’ protégé Peter Bogdanovich—practicing artists who can’t help but comment on their art.

ONE-MAN BAND, CALLOW'S latest, follows Welles through the ‘50s and ‘60s, as he casts about Europe for money and improvises his way through stage productions like Moby Dick and films like Othello, Mr. Arkadin, and Chimes at Midnight. The book reinforces an alternative narrative, first championed by the French and later popularized by Bogdanovich. Welles, his partisans argue, never stopped making masterpieces, even if some were marred by a lack of resources. If anything, he learned, like a sonneteer, to work within ruthless constraints. When costumes failed to materialize on the set of Othello, Welles deployed towels and relocated Roderigo’s murder to a Turkish bath. When the set itself failed to materialize, he relocated his adaptation of The Trial to an empty train station.

“He also rejects postmodern cant—for example, undergrad-grade assertions that people are unknowable and thorny concepts like ‘truth’ require tongs.”

The stories are fascinating, but the best passages in One-Man Band are energized by Callow the Critic: they record gestures of power and feebleness. He’s particularly incisive about Welles’ acting, which Welles, so often absorbed in his productions, usually left to the last minute. “[T]o climb the mountain called Othello, neither physical appearance nor charisma nor even inspiration will suffice,” observes Callow.

It requires unrelenting hard work, mentally, physically and vocally. Welles seems never entirely to have mastered the text, so inevitably he was always enslaved to it, never able to ride it, always hanging on for dear life, or putting on the brakes to slow the play down to the speed of his own thought rather than Othello’s. He was also unable to reveal the character’s detailed progression through the play or indeed its hidden strata….In the phrase of actor-laddies of yesteryear, he lacked puff: the stamina, both physical and vocal, demanded by these great roles. He was, in a word, unprepared.

There’s much to admire here—repetition (“always enslaved to it, never able to ride it”), metaphor (“hidden strata”), a handle on the historical lingo (“puff”), and confidence funneled down to a phrase (“in a word”). Elsewhere, describing Welles’ scene-stealing part in Compulsion, Callow pumps plasma into a cliché: “Like the great Victorian stars, he speaks slowly and softly, creating time and space around himself. It is unquestionably ham, but it is very thinly sliced.” Even seemingly throwaway phrases like “The slow, selfish growth of a performance within an actor”—a growth Welles almost never allowed himself the time to cultivate—seem loaded with lived experience. Like those of the best critics, Callow’s formulations are both apt and inventive. And there are so many to admire. “Like many a critic before him and since, Tynan failed to understand that his darts, so blithely fired off, actually drew blood.” Callow can string a pointed insight, of universal worth, at will.

“Great criticism is fantasy archaeology. You can’t help but absorb Callow’s excitement as he excavates failed collaborations, missed opportunities, lost works of art, what could have been—the endless counterfactuals that fork off from Welles’ many baffling decisions.”

But because he tends to be exacting, the reader tends to trust his praise. His grave judgments, which wreathe certain works in darkness, ensure his celebrations sparkle. Callow is no fanboy, and refuses not to find fault with faulty gems like Othello and The Trial. (I’m a Trial apologist myself, but would die for Callow’s right to file outrageous copy.) The book builds towards Callow’s appreciation of Chimes at Midnight, Welles’ love letter to Shakespeare’s Falstaff, a masterpiece that hasn’t always been easy to see. The unfinished Don Quixote—“his notebook, his diary, his cinematic letter to himself”—is another Wellesian project one wishes were more accessible, at least when Callow writes about it. Great criticism is fantasy archaeology. You can’t help but absorb Callow’s excitement as he excavates failed collaborations, missed opportunities, lost works of art, what could have been—the endless counterfactuals that fork off from Welles’ many baffling decisions.

Callow’s biography has grown more fascinating and useful with each successive volume. The Welles of the first book—the god-like prodigy who let there be Kane—we already know about. But the unapologetically purple concluding sentences of One-Man Band look forward to the final, more beclouded years of Welles’ life—and threaten to make fanboys and -girls of us all:

[H]e was thrusting out towards unknown regions, dreaming celluloid visions, unceasingly toiling over the chance to extend the ribbon of dreams, as he had so memorably described film-making. It was an epic journey to match the epic of his first fifty years, and the fact that there was so little to show for it is at once tragic and oddly inspiring: there is a nobility, a selflessness to the quest.

Callow, of course, will have more to show for his efforts. His biography of Welles, once completed, will likely be his masterpiece. (Curious readers should also check out his slim, perfect monograph about Laughton’s only film, The Night of the Hunter.) But One-Man Band isn’t simply an effort to bring a god to ground; it’s a great work of criticism, too. Callow cuts through the smoke that swirls around Welles—that Welles himself often generated, that seemed to pour forth from his iconic cigar—and screens an image of an artist we’ve never quite known.

JASON GURIEL co-edits Partisan. His recent culture writing has appeared in The New Republic and The Walrus, and his latest books include a collection of poems, Satisfying Clicking Sound (2014), and a book of criticism, The Pigheaded Soul: Essays and Reviews on Poetry and Culture (2013).

WHAT TO READ NEXT: "At some point, the best actor of your generation is going to show up onscreen out of shape, out of touch, and in it for the money."

BROOKE CLARK reviews Seamus Heaney’s Aeneid Book VI